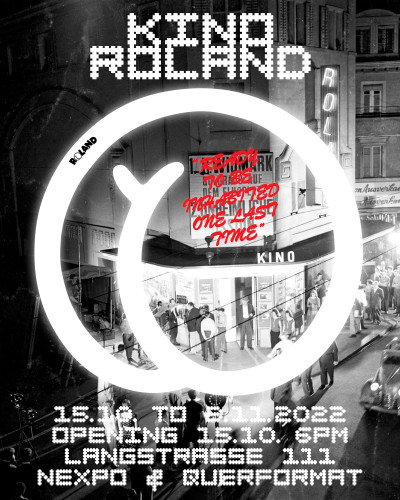

Kino Roland

Ready To Be Inhabited One Last Time. Eine Einladung von Nexpo – la nouvelle Expo und Querformat.

15. October – 3. November 2022

Opening times: Wed – Sat, 6 to 9pm

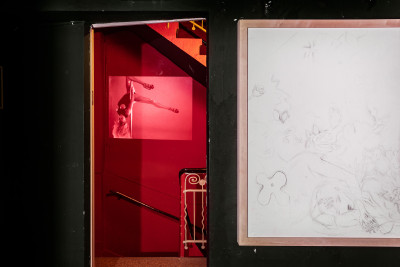

Kino Roland is one of the oldest cinemas in Zurich. Built in 1881, it became a sex cinema in 1978. Due to the digital transformation, but also due to broad processes of gentrification, it is now empty. In the last ten years, property prices around the cinema have more than doubled and the proportion of foreigners has dropped by around 20% since the mid-1990s.

In search of possible venues for the next national exhibition Nexpo, we explore places of change and seek the new in the existing. We ask: How do we live together in the 21st century? In collaboration with the collective Querformat, the former cinema will be put to an investigation. It becomes the starting point for a discussion on how corporeality is negotiated in urban and public space.

For one last time, we invite you to inhabit the void of Kino Roland with us.

Artworks by Mathilde Agius, Ellen Cantor, Azize Ferizi, Dese Escobar, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Larry Johnson, Monica Majoli, Reba Maybury, Dean Sameshima, Annie Sprinkle; installation by Querformat; kiosk by Tatjana Blaser and Madame ETH; merchandise by Mistress Rebecca.

15.10.22, 6pm: Inclusive Monuments? Preservation of Sex Cinemas

Opening and talk by Prof. Dr. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes (EPFL) and Prof. Dr.-Ing Silke Langenberg (ETHZ)

Performance Dispositivo de Saturación Sexual by Candela Capitán

21.10.22, 7pm: Faster Than An Erection

Talk by Reba Maybury and Cassandra Troyan

22.10.22, 6pm: Samuel Delany's Porn Worlds

Talk von Tavia Nyong'o (Yale University)

28.10.22, 6.30pm: CYBORG MANIFESTO_2

Talk by Monica Majoli

8pm: Performance by mercedes_666

29.10.22, 6pm: Leaving the Movie Theater

Talk by Damon Young (UC Berkley)

3.11.22, 6pm: Kino Roland Barthes

Closing talk by Bruce Hainley (Rice University)

Kino Roland is closing down. As a sex cinema running for more than 40 years, it has been providing pornographic material until recently, and hereby complementing the array of sexual services at Zurich’s Langstrasse. It has been a mediating institution within the city, one that modulates and regulates the contemporary sexual subject through its semiotic-technical government. Its bricks, neon signs and mural paintings have been in charge of reproducing the biopolitical norm of the heteronormative patriarchy, inducing sexual excitement in the male viewers while unveiling the disobedient nature of sexual desires.

The porn theater delimitates a territory under the exclusive dominion of the male subject. Women are notoriously absent, appearing only on screen or on the mural representations of lesbian intercourse via the male gaze and as pleasure giving devices. This fundamental erasure of womanhood is well illustrated by Audre Lorde, claiming that women’s erotic power is oppressed by the pornographic. The symbolic representations of patriarchal power in heterosexual pleasure have led feminists such as Andrea Dworking to reject pornography as a whole practice, having identified a clear link between extreme sexual violence against women and the consumption of pornography. Other feminist figures identify a radical liberating potential within porn. For Virginie Despentes, “the porn actress is the liberated woman, the femme fatale, the one who turns heads, who always provokes a strong reaction, be it desire or rejection.” There is no doubt, however, that female actresses are being subjugated and exploited by the porn industry. While the anti-pornography movement runs the risk of defining the female body as inherently unable to emancipate through porn, Despentes states that “the only moral issue…is the political aggressiveness with which these women are treated offstage.”

Built in 1881, the transformation of Kino Roland into a sex cinema in 1978 takes place in an already developed pharmacopornographic capitalism, as posited by Paul B. Preciado. It has been one of the visible architectural devices of the pharmacopornographic regime within public space. Its closing down might just signify a broader retreat of porn consumption to the domestic and the digital space. Pornhub, XVideos and Only Fans have transformed every bedroom into a sex cinema and every inhabitant into a potential porn actress/actor.

However, what happens in the dark room might have been more complex than watching and wanking. Random encounters between men seeking for pleasure emerged out of the must of sharing a physical space to watch porn. Samuel Delany has written about his crusing experiences as a black homosexual man in the sex cinemas along the 42nd street in New York, just before they were demolished as a result of the Times Square’s zoning plan. Those spaces have fostered cross-class and mixed race social contacts in the shape of aromantic intimacy. The complex social network around them has stabilized different communities while maintaining their heterogeneity. Four years after the book was published, the newspaper “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” reported eight male immigrant sex workers being arrested for providing sex services in Walche, another Sexkino in Zürich run by the company that operates Roland.

It might not be coincidental that the closing down of Sexkino Roland overlaps with a broader, ongoing process of gentrification at work in Langstrasse. Among the sex cinemas in Zürich, “Stüssihof” has already been converted into a children’s cinema in 2014, while “Sternen Oerlikon” has become a gastronomy venue, imagined as a meeting place for “the local community”. Gentrification goes hand in hand with the disappearance of sex in public spaces. The transgressive character of porn mentioned above is directly at odds with the process of urban homogenization. As the collective “Dangerous Bedfellows” states, The battle over public sex is “also about real estate and big business”. As they pointed out, “restricting sexual expression in public space is about artificially inflating property values, "gentrifying" certain neighborhoods while turning others into commercial dumping grounds, and destroying the sexual culture that residents and tourists have built—and governments have fought—for decades.” When gentrification arrives, sexual and uncomfortable contents are replaced by family-friendly entertainment. The foundations of the pharmacopornographic regime have to remain underground, either in the urban or in the cybernetic depths.

The closing down of Kino Roland and the current state of abandonment of the building opens at the same time a void within the public space of the city. Being no longer a potential cruising interior, nor a physical place which supports the biopolitics of the pharmacopornographic society, it leaves a void full of potentiality, ready to be inhabited one last time.

A few years ago, Paul B. Preciado pronounced a speech in front of the “Ecole de la Cause Freudienne”, announcing a “period of unprecedented historic importance”, one in which “the epistemology of sex, gender and sexual difference is mutating” (Preciado, 70). Sexkino Roland could be a mark of a collapsing epistemology (19), and the building could mutate alongside it, thus marking the passage from sex, gender and sexual difference to an endless number of differences of bodies, of unidentified and unidentifiable desires.

Photos: Nelly Rodriguez